How to Influence What You're Going to Get

Back in 2017, we published an article that mentions “rules as boundaries.”

To the degree possible, set rules as boundaries. In other words, whenever possible, make broad rules about what not to do rather than overly prescriptive rules about what must be done. Then reward results, not rule following. Leave room for affordable mistakes. Follow them up with purposeful learning. People need room for ingenuity and creativity. The business reason for this is employee engagement.

Since then, we have encountered some curiosity about the term and how to actualize it in practice. At the same time, we have clients who are on opposite ends of the spectrum with regards to what we call the “operating box.”

The operating box is defined by the boundary rules and encompasses a person’s allowed space for operational behavior and decision-making. We currently have one client whose boxes introduce unnecessary risk, and one whose boxes restrict innovation and agility.

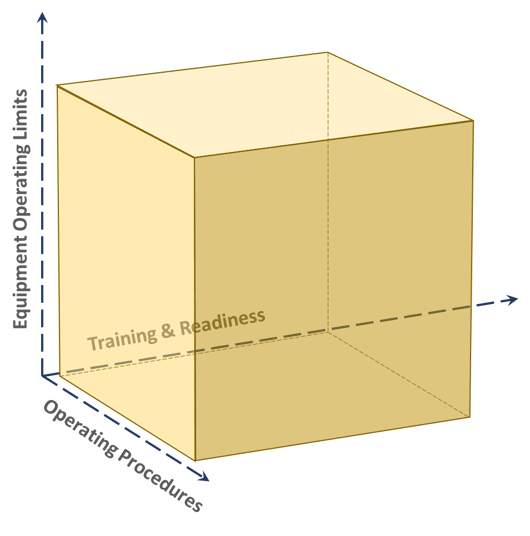

Let's start with a visual:

The box is defined by limits on three axes:

- Equipment limitations.

- Training and readiness of the person or people in question.

- Operating procedures as imposed by the organization or regulatory forces.

People operate—making decisions and taking actions—in the box defined for them by these limits. Different people in different situations generally have different boxes, as imposed by their leadership.

Within the box, we want good judgment and learning to take place. The boundaries are “do not cross” rules. We want to make as much room as possible for good judgment, because ingenuity and innovation depend on it.

As an added bonus, the management burden incumbent upon a person’s supervisor is smaller for bigger boxes.

Two things you can count on from essentially any human being: error and ingenuity. The challenge, then, is in making room for more ingenuity by imposing a bigger operating box, we also make room for more error. The bigger the box, the bigger the errors can be, and the more problematic the consequences of those errors.

The trick, then, is to size a person’s operating box so they have room for ingenuity and affordable mistakes, from which they and the organization can learn. And to keep resizing the box over time with training and experience, trending towards bigger boxes.

So how do we properly size an operating box, then?

First, keep it cubic. We want the level of competency training and readiness to be matched properly to the procedures governing behavior and, to the degree possible, the complexity and capability of the equipment being used.

We do realize the axes of the box are measured in different units, so “cubic” becomes meaningless pretty fast if you look too closely at the metaphor. Nevertheless, parents, coaches, and the military shape cubic operating boxes intuitively all the time.

When leadership errors lead to an improperly sized operating box, sooner or later the person in the box makes an unaffordable error, or is unable to operate at her peak capability.

Imagine a professional racecar driver at the starting line of a NASCAR track amongst his competitors…sitting in the cockpit of a steamroller. You easily recognize the equipment limitations of this operating box are not well matched to the competency of the driver or the procedural limitations of a NASCAR race. This “flat” box leads to underperformance.

If instead, the competency/readiness limits are too restricted, we end up with a box that’s flat along a different axis. For example, in the same NASCAR scenario, if we put an overconfident teenage boy with a new driver’s license behind the wheel of a race-ready automobile, it might be unsafe for him, his competitors, and the spectators. So this flat box leads to unmitigated risk.

What if the procedural limits make the operating box flat? This is not uncommon in highly regulated and/or mature industries. Sticking with the NASCAR theme, we’re now talking about highly trained drivers, finely tuned cars, and a speed limit of 55 miles per hour.

This flat box stifles innovation because “drivers” are unable to explore their own limits—they remain unchallenged and therefore unmotivated to expand their limits. The organization follows the individuals’ slide into complacency and slow death.

In all three cases, the operator in the box is demotivated and naturally tends to disengage.

As an example of successfully shaped operating boxes, I’ll use naval aviation. When we were young, untrained aviator wannabes, the organization stepped us through increasing levels of competency and equipment, with matched decreasing levels of procedural restrictions.

Over a period of about two years, we started with simulators, flew turboprops, then slow jets, then fast jets with small weapons, then big fast jets with big weapons.

During this time, our training was commensurate. We had ground school, flights with instructors, check flights, solo flights, and additional training in weak areas if necessary. The cycle would repeat at each new airplane and each new skill in a given airplane type. We also got sorted along a continuum of competency. Students deemed highly competent usually ended up flying the aircraft of their choice (typically carrier-based jets).

Operating procedures opened up throughout the process, as well. First, we just learned to fly a plane. Then to fly at night. Then to fly aggressively. Then formation flights, daytime low-level flights, day carrier landings, nighttime low-level flights, and finally night carrier landings.

There is a somewhat abrupt transition in the progression of operating procedures most of us remember as transformational. It was the first hint we were to be trusted as having “good judgment.” Aviation training starts with very prescriptive procedures, including details as fine as throttle setting numbers for each maneuver. At one point, instructors stopped telling us those details. Naturally, we would ask, “What’s the throttle setting for that?” Their answer, every time, to a man: “Whatever it takes.”

They had stopped telling us what to do and started telling us what results we needed to get.

If they had taken that approach too early, there would be a lot of dead students. If they had taken it too late, we would not have the reliable and safe high performance we have in naval aviation in spite of the risks.

Also illustrated by the naval aviation example is that, to be effective, sizing the operating boxes in an organization should be purposefully coordinated. Which means competency assurance is best done with a dedicated program.

That said, perhaps most operating box sizing is done when line supervisors make this judgment call: “Am I setting that person up for affordable mistakes?” (Not zero errors and not unaffordable mistakes.)

This brings us to what ought to be going on inside the operating boxes: good judgment and learning.

Good judgment doesn’t emerge from a history of zero errors. So errors are actually required, but need to be affordable. Operators need to know a) errors are to be expected; b) not all errors are created equal; c) the point is to learn from errors as an organization.

When incidents do occur, after the dust settles, the next question the organization must ask itself is, “Did leadership shape the operating boxes properly?”

If, instead, operators expect their errors, when discovered, will be met with punishment of some sort, they will very naturally prioritize a lack of errors. The only way to do that is to deprioritize innovation. And when they do make errors, they will tend not to report them. In that scenario, both innovation and organizational learning suffer.

To counteract this pattern, organizations can make learning an organizational competency. The cornerstone for a learning organization is a human factors-based investigation program. With a solid HFACS program (“learn from errors”) paired with a strong leadership development program (“limit errors to affordable ones”), organizations can purposefully recreate themselves as resilient, reliable, and high performing.

In summary, High Reliability Organizations (HROs) will have these programs in place, at a minimum:

- Leadership Development. It must be multi-tiered and self-perpetuating. One of the most important products of an HRO is competent leadership.

- HFACS. Cultural factors must be viewed as causal factors. Seek deep learning for broad application.

- Competency Assurance. This is a key component in keeping operating boxes “cubic.” Properly done, it leads to and engaged, agile workforce.

These programs, in concert, allow for agile, innovative, decentralized, high-quality decision-making. What company wouldn’t want that?

Want to activate innovation in your organization? Click here to learn more.

1200 Corporate Drive, Ste 170

1200 Corporate Drive, Ste 170